Articles

This portion of the site is dedicated to my writing about games and game design. Everything I write is grounded in a wide variety of experiences I’ve had in the games industry, but I also recognize that my viewpoint can hardly be universal. Games are more art than science, after all, and art is open to everyone’s own interpretation. Still, I’ve picked up a few things over the years, and I’m excited to share them with anyone who is interested!

2024 in Game Design

2024 was a busy year, and here are some of the major project milestones!

Well, 2024 was a busy year for me, as evidenced by the (ir)regularity of blog post updates and progress on personal projects. I’m trying to be positive that I managed to publish two whole articles in 2024, which is better than can be said for my languishing my Warhammer Fantasy army.

But it was a big year for three of my professional projects, and I’ll give a brief rundown on each of them. Along with each synopsis, I’ll discuss some musings that I took from each of these very different design experiences, which I’ll boil down to a question to guide my future projects.

Star Trek: Into the Unknown Released!

Star Trek: Into the Unknown is a game that Michael Gernes and I designed for WizKids. It’s available now, but we started all the way back in 2021 (how long ago that feels). For a bit of background, Michael and I have known each other since 2011, and have worked together on miniatures games for the better part of a decade. We’re also both lifelong Star Trek fans, which made this project especially exciting. This project also gave us the chance to work with familiar faces like Alex Davy (during his tenure at WizKids) and John Shaffer. So we had a ton of game design experience behind us as we set about crafting a deeply thematic, story-driven Star Trek miniatures game experience.

“Engage!”

One of the most interesting considerations of Into the Unknown was the design spec: WizKids asked for a game that felt truly distinct from Attack Wing (their last venture into Star Trek fleet games) and other existing miniatures games about starships. After a great deal of discussion, Michael and I came up with a direction: a game that focused on emulates the feel of an episode of Star Trek rather than focusing exclusively on battles in the Star Trek setting. Of course, battle would still be part of the game, but we set our course for a game that would encompass more than just armed conflict. This led to a few of game’s key innovations: its added focus on officers as a principle agent of actions in the game, the use of directive cards to reflect each factions ethos and rules of engagement, and a two-act structure for each game with a midpoint complication that can change the terms of the mission.

Designing the mission system for Into the Unknown lead me back to the drawing board when it comes to deciding what player incentives should look like. Michael and I spent a lot of time discussing how incentives should help the player immerse themself in the Star Trek experience and I’m very proud how we aligned gameplay with the themes of Star Trek. This exploration also left me with the question: If I’m not adapting a universe but instead creating my own, what do I want to ask players to care about?

Stonesaga Approaches Completion

Speaking of fully original stories, Stonesaga is chugging along. Well, maybe trudging along? Prehistoric people didn’t have trains. The team is in the midst of final file review as I write. As the game gets more and more realized, it’s amazing to think about all of the hard work the team has done to elevate the project, from art to graphic design to sculpting to box and tray design.

Core set and expansion miniature proofs for Stonesaga.

I’ve written a bit about the Stonesaga process over the last few years, although less than I’d originally hoped I would. I had aspirations to document a lot more of the process in real time with blog posts. But it turns out that writing over 60,000 words of story outcomes to go into a board game saps a lot of my energy to blog about the process of writing those entries. Who could have imagined that there’s a limit to how much someone can productively accomplish in a single day?

Image unrelated, probably.

Stonesaga sits in a very different place on the creative spectrum. Open Owl Studios head Brendan McCaskell had a clear concept (“a prehistoric fantasy board game where you draw on the inside of the box”), but development of the setting and mechanics were in large part left to myself, co-designer Luke Eddy, and others on the project. As someone who has predominantly worked on licensed (or at least preexisting) settings, this was a new experience.

It was also a very different creative pipeline than I’d experienced before. For most prior projects I’d managed or been involved in, going all the way back to my days as an RPG producer at FFG, there were clear steps for each creative task. When I needed to commission a map for an adventure, I had to get a brief for that map off to the Art Department long before the writer delivered the final manuscript. The structure didn’t really allow for a step where all contributors got into a room to brainstorm what would be the coolest things both narratively and visually. A siloed structure like this is, realistically, necessary for a studio juggling dozens of projects.

In contrast, Stonesaga was a small team, collaborating closely at all steps. Art often directly influenced flavor and game mechanics. This back-and-forth iteration across disciplines during the whole process isn’t necessarily scalable, but it also made a lot of the coolest parts of Stonesaga possible. For example, art-informed gameplay elements like the Foraging cards and the hidden omens wouldn’t have evolved in a siloed environment. So for future projects, I want to ask: What design assumptions of mine about what is possible to accomplish are wrapped up the most familiar process? And how might the structure of each individual project create opportunities I have overlooked?

Consulting on Cosmere RPG

And on the topic of large, collaborative creative teams, I was lucky enough to be a consulting designer for the Cosmere RPG by Brotherwise Games. The largest tabletops games Kickstarter to date hardly needs an introduction, but what is a consulting designer, anyway?

This isn’t an embedded video, I just wanted a picture of that funding number.

I don’t have a hard-and-fast definition of consulting designer. But I do have a clear goal for when I take on work as a consulting designer: my job isn’t designing the game, it’s making sure the designer(s) are able to do the best design work possible. This means acting as a sounding board for brainstorming, an interrogator of ideas, a guardrail against things getting too out of hand, and a font of ideas when creativity runs dry. It’s a lot like what anyone sitting in the RPG or Minis room would do for our coworkers at FFG between our own tasks, but with a bit more procedural rigor.

I came onto the project early, meeting with Johnny O’Neal in late 2022 to discuss his concept. In essence, Johnny wanted to draw upon my expertise as he worked through the basic game profile and concept, and then wanted my voice in the room throughout the project to maintain a degree of continuity during the design process. At this stage, being a consulting designer meant contributing to the vision and product design as Johnny solidified the direction of the game.

As Andrew Fischer took on the role of Lead Designer and the project matured, the role of consulting designer shifted, too. I was on the RPG team with Andrew Fischer while he designed Only War (and then Age of Rebellion, then End of the World), and we worked closely on these projects. As I mentioned above, one of the best features of FFG’s RPG team was the way that everyone would pitch in on major projects, lending their practical expertise to specific aspects of the project. I spent a lot of my time at this stage focused on the interaction between Heroic and Invested paths, a similar balancing act to the one I’d previously managed in games like Legend of the Five Rings.

Now that the project is well into maturity, my role as a consulting designer has evolved yet again. System design is largely finished, but content design continues! Maintaining continuity between the system design and the content design that builds upon it is one of my major tasks at this stage. Expanding a system without overwhelming it is a delicate process, and one where collaboration and discussion are key to success.

The thing about Brotherwise’s ambitious Cosmere project that got me thinking the most, though, is the way Brotherwise approaches working with Dragonsteel. From the preliminary meeting in Utah to the Cosmere RPG’s incredible presence at this year’s DragonsteelCon, the amount of partnership engagement I’ve seen really sets the bar. This leaves me wondering: What are the ways games can be more than just adaptations of other media, but truly complimentary experiences? How can integration with wider stories make games better, and how can games enhance stories in other mediums?

And that about rounds out the announced major projects I worked on in 2024. I do have a couple of other things in the wings that aren’t ready for the public quite yet… but check back later in the year!

Three Personal Lessons from X-Wing

Three things I learned about life from my first go-round making rules for plastic spaceships for work.

Three Lessons from X-Wing

In my last post, I reflected back a bit on my time with X-Wing. Today, I want to share three anecdotes from this time that gave me insights beyond the game’s considerable wingspan. I’ve broken these down into different stages: a beginner lesson as I learned the game, an intermediate lesson as I gained conceptual mastery of it, and an advanced lesson as I reflected on the “why” of it all.

[Beginner] Give Yourself Room to Maneuver

Fragment (Depicting Airplanes) (Dress or Furnishing Fabric), 1920-39, Unknown

Also a pretty accurate depiction of my first game of X-Wing.

When I took the assignment to work on X-Wing, one of the first things I did was play a bunch of practice games to get up to speed. And in the first of these, I played against Alex Davy. Naturally, as most first-time players do, I ran my ships into each other immediately after setup, causing my plan to fall apart, at which point Alex’s ships swooped in to crush me. In the wake of my multi-ship pile-up, I remember Alex said “You’ll learn how to avoid doing that,” or something to that effect. And he was (mostly) right. Over time, I got a sense for the spacing of the maneuvers.

And, as I designed further waves of X-Wing, I started to discover the importance of creating that same room to maneuver in design. A lot of X-Wing’s troubles when I joined in late First Edition stemmed from the early choices that created hard bounds on the game, like permanently fixed points values or high-end, absolute effects like 360-degree firing arcs. Even the 100-point scale for list-building made it hard to carve out a place for new cards. Second Edition’s main design goal was giving the game room to maneuver in the very long term without crashing into itself. Tools like adjustable points values, systemic curtailing of effects that fed fun eutrophy, and subtitles for pilots to allow repeatability of iconic characters were all meant to give the game the space to fly free for as long as it needed.

In life, maintaining flexibility for myself has been important, too. As I discussed in the last post, it would have felt safer in some ways to stick to RPGs rather than shift into a different field of games. But by expanding my options with experience on X-Wing, I was able to give my career the room it needed to reach new spaces and give myself the confidence to take the chance on new projects. By entering a new space, I made personal and professional connections with tons of new people. I already knew many of the names and faces in the RPG space, but miniatures games were a whole new field, and both Stonesaga and Star Trek: Into the Unknown stem in part from connections I made by working on X-Wing.

[Intermediate] Consider the Costs of Jousting

Boat Joust, Jean Rigaud, 18th century

This was honestly the best public domain jousting image I could find. It both was and was not what I expected when I clicked.

For someone who has played a lot of X-Wing over the years, I don’t win all that often. Even at my best, I would say I never got past “competent enough not to crash my ships into each other while executing a plan.” Alex and Frank, my elders on the game, could go to tournaments and place reliably, as could Brooks, who joined after me. But executing visual-spacial challenges is just not one of my strengths. However, it was my job to understand the game at various levels, from basement tables to Worlds. Eventually, I became extremely versed in the tactics and strategy of X-Wing and I learned how to mentally engage with the challenges players better than myself faced. I’ve written a bit about these competitive players in the past, and how much I enjoyed working on a competitive game despite not being much of a “shark” myself.

As you start playing X-Wing, you develop a preferred setup and flight pattern for your list. At first, your losses are attributable to failures of execution (like my ill-fated ship pileup in that first game with Alex). But once you can execute your approach reliably, you start to notice something important: you don’t always win, and more importantly, there’s a specific pattern the among the games you lose. From the outset, if you and your opponent just fly straight at each other, guns blazing (often called “jousting”) somebody has a mathematical advantage. Assessing how your list fares against your opponent’s in a joust is a crucial skill in X-Wing. Essentially, this is the same concept as the famous Magic: The Gathering strategy question of “Who’s the Beatdown?”, seen in Space Owl’s X-Wing version “Who’s the Joust?”, too. When you’re outgunned, deciding to just joust is unquestionably easier than adjusting your attack vector on the fly, but shifting the terms of the engagement in your favor is more likely to give you the win in the end.

About a year before I left FFG, I had been working on X-Wing for roughly four years, and I found myself asking “Where will I be in five years if I stay on this course?” And I was uncomfortable with the answers I imagined, because while I loved my job, my team, and working on X-Wing, I also wanted to create games of my own - something I just didn’t have hours in the day to pursue. Doing something new looked like a huge risk. But what I wasn’t considering, which I can now look back and see clearly, is that there was a huge risk to not doing something new, too.

Expanded beyond zero-sum situations like 1 on 1 competitive games, I think this lesson looks like this: following a conventional path or established plan is often appealing, and certainly can be valuable as you build your skills or experience. But it can also be an unconscious constraint, enabling you to forget that that the conventional path is still one you are choosing. You aren’t locked in, and taking a moment to ask “Is this course the best one for me?” might reveal alternatives lead to more appealing places.

[Advanced] Choose to Optimize for Fun

The Flying Philosopher, Unknown, estimated 19th Century

This probably isn’t an efficient way to fly, but he does look like he’s having fun.

Designing X-Wing meant playing a lot of games of X-Wing for reasons other than fun. From testing the feel of new mechanics to trying out competitive lists in preparation for balance updates, most of our games weren’t primarily played for fun. And yet fun would sneak back in. Sometimes, this just meant the whole room cheering when Luke blasted Darth Vader off the table with a million-to-one shot in a test game. Other times, we would build elaborately crafted lists around an esoteric joke or try absurd combinations just to see what would happen. We would see an interaction at the table and then say “Hold on, what if the Vulture droids could land on asteroids?” and hop back to our computers to type up the ability. Of course, it was work - we had deadlines to meet and problems to solve, but some days the urge to introduce fun for its own sake was just irrepressible.

There’s a game design saying (often attributed to Sid Meier and/or Soren Johnson) that “Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game” and, as a corollary, “One of the responsibilities of designers is to protect players from themselves.” The saying sticks around for a reason: it’s solid, insightful advice. Individual players will often choose the path of expedience over fun. A player base of sufficient size and motivation will find every single crack in your system. Fun can easily get lost in the hustle and bustle of optimization.

But I think back to those office games - we were literally playing for work, and yet fun would bubble up. We’d choose to make the games more fun than we needed to. In turn, those ideas would often percolate back into new designs. And beyond the office, people were doing this for themselves without our involvement. Individual choices by players matter and people can even (un)optimize the fun back into a game that has gotten stale to them. As often as I talked to competitive players who were running something “meta,” I’d encounter other, equally competitive players fielding creative, highly personal, or just “janky” lists that threw the paradigms of the month out the window in favor of self-expression or fun. I met some players who specialized in one specific ace regardless of that character’s standing in the meta, and others who would jettison their old winning lists and take big risks just to keep things fresh because they knew they loved novel experiences. And from the fan-inspired Aces High or “Mario Kart”-style events at the side tables in the X-Wing hall, there are countless examples of ways people have tweaked the game itself to optimize fun to great results. I saw people choose fun all the time, and I loved those moments.

So when you’re approaching a new list, a new game, new hobby, or a new project, really ask yourself why you’re doing it and what you want to accomplish. If one of your goals is to enjoy yourself, think about how you can actively facilitate that goal. Don’t just make a plan that averts failure, also consider how your plan encourages enjoyment. Build having fun into your strategy at the foundation. And if your assessment reveals that fun really isn’t a priority for you, understand what else is motivating you and ask yourself how best to fulfill that.

A Farewell to S-Foils

In light of the news of the conclusion of the current era of X-Wing, I wanted to reflect back on this game and its impact. Not on miniatures games, but on me.

I worked on the X-Wing Miniatures Game for several years, from the Shadow Caster in First Edition through most of Second Edition’s lifespan. Working with the miniatures team at FFG did a lot for me – professionally and personally, I look back on the time I had with that team and with the wider X-Wing community very fondly.

So in light of the news of the conclusion of the current era of X-Wing, I wanted to reflect back on this game and its impact. Not on miniatures games, but on me. Today, I’ll provide a bit about my personal history with the game. In a subsequent post, I’ll dive into three lessons I took from my time on X-Wing that extend beyond the game’s wide wingspan.

Parallel Flight

Photograph of Sam Gregor-Stewart, Andrew Fischer, and myself playing some Commander at GenCon 2015

Oddly (or perhaps fittingly), X-Wing and I had tenures at Fantasy Flight Games that lasted roughly the same amount of time. When I joined the RPG team in 2011, X-Wing was in its early days of development, and I participated in some of the Wave 1 playtests. I remember the buzz around the office as we awaited news of the sales on the first print run. Would this big bet in a new gaming space pay off? In retrospect, the answer would end up being a resounding “Yes,” but at the time, it felt far from assured. But once the first print run sold out immediately, the writing was on the wall: X-Wing was going to be big. And beyond its sales, it was one of the products of that era that helped launch the studio to new heights. As Andrew Navaro discussed on the Earthborne Rangers Podcast, X-Wing was a huge part of FFG’s development as a studio, bringing about advancements in design, distribution, production, organized play, and more.

My path also diverged from FFG’s around the same time X-Wing’s did, in late 2020. Going freelance was a big life step for me, and it was apparently well-timed. I met Brendan at OOMM Games (now Open Owl Studios), and, of course, we all know how that went (but if you don’t for some reason, hey, check out Stonesaga!) This new course also gave me the opportunity to pursue other exciting opportunities like Star Trek: Into the Unknown with WizKids and design consulting on the forthcoming Stormlight Roleplaying Game from Brotherwise Games. I’m excited to write more about these games in the coming days, but right now, we’re here for X-Wing.

Jumping into the Cockpit

Star Wars Celebration 2017

At FFG, I came to X-Wing largely by chance. As I mentioned, I’d playtested it early on in my time at the studio. However, at the time, I tended to play hobby-oriented wargames like Warhammer Fantasy (now The Old World), Dust Warfare, and, of course, my longtime frenemy Warhammer 40,000. I bought ships for my friends as gifts, but beyond a few teaching games, I didn’t really touch the game for years.

But then, years later, a chance to work on X-Wing came up. Frank Brooks and Alex Davy had carried the game line for years, and wanted opportunities to explore other projects (which eventually gave us things like the Fury of Dracula reboot and Star Wars: Legion). I knew Star Wars well from my time producing RPGs, and I knew miniatures games, so I was asked if I would want to take on X-Wing. It felt like a risk. I knew I liked making RPGs, and I was working toward being lead designer on a game of my own. But I was also curious to see what this new opportunity might bring. I decided to take a risk.

This turned out to be a fantastic decision. The growing miniatures team at FFG was a fantastic creative group, from fellow designers to producers to sculptors to marketing to organized play to the massive and deeply passionate playtesters. I’ve written about design lessons from X-Wing and other games before, but I want to emphasize that these games happened because of the hard work of a ton of people well beyond the design team. It was a group effort extraordinaire, and I’m honored to have been a part of it.

Beyond everything we did in the studio, I was always amazed by the level of passion and creativity I saw players of the game bringing to the table (often literally). In RPGs, I rarely got to see the effect of my work so directly or dramatically. For RPGs, we’d get emails and letters periodically and we ran games at GenCon, but RPGs are predominantly played in the home, privately. Nothing compared to the thrill (and trepidation) of walking into a tournament hall packed with hundreds of people. The scale of interaction with the players was just totally different.

And at these events, people would dress up as their favorite pilots, modify and paint their ships, create their own game formats for events, produce absurdly well-made tokens and alt-arts for their opponents, and hone the competitive art of the game to a razor edge. It was a little intimidating to be responsible for an important part of a game that so many people cared about, especially when my decisions were under scrutiny. I didn’t get it right every time on design, and I learned a ton from the mistakes I made. I learned more about running a fake economy than I ever thought possible. But every time I went to an event, I was reminded exactly what made my job really special: the community of people who cared enough to come out and play it.

The Twisting Trails We Leave

The latest batch of forces painted and ready to scrap with some Cylons or Rebels. Now to print up that Rygel card…

Since leaving FFG, I have continued to watch the X-Wing community, mostly from afar but with the occasional podcast appearance or catch-up with longtime players. And through the ups and downs, I’ve been pleased to see a consistent trend over the years: people want to play X-Wing and they find a way to make that experience awesome for themselves and others. This isn’t true of all games. Sometimes even big hits vanish quickly for a variety of reasons: player fatigue, lack of availability, or dissolution of the community.

But other games endure, living on at the table long after their days as products are over. One of my favorite games, Mordheim, maintains a highly engaged core community of players despite minimal support for the last two decades and a hard-to-acquire rulebook. I didn’t even discover Mordheim until long after its days on store shelves had passed. But passionate players have kept the fires burning, taught me how to play, and helped me set up a warband. So while this might be a “Farewell to S-foils” in a certain sense, I don’t think it’s an ending. I just see too much excitement in this community for the game to go quietly into the night. I’ll certainly keep putting X-Wing on the table (extremely casually, mostly with homebrewed ships from whatever sci-fi show I watched most recently - bonus points if you recognize the ships above). If you love the game, I hope you do, too!

Late Update: My good friend Gavin Duffy, an X-Wing producer for much of my time on the line, has sent me some wonderful pictures of the team I previously didn’t have! Check us out eating hot wings and playing mini-golf!

Hot-Wings, TMG, photo courtesy Gavin Duffy

Arc-Dodging Hazards on the Green, courtesy Gavin Duffy

On Acorns

Acorns and humans go way back. These tough-shelled, bitter nuts aren’t a staple crop for most humans today, but across history, they’ve been vital to survival for many groups. Even today, they’re used to make everything from bread to noodles to jelly. They (and hazelnuts) are one of the main crops I looked to when designing the nut resources that are so crucial to many strategies for survival in Stonesaga.

As I’ve worked on Stonesaga, I’ve read a lot about human history and prehistory. One thing that research has reinforced is that the world has changed a lot in the last 20 thousand years, in no small part due to human activity. But sometimes the expanse of ages doesn’t feel quite so impenetrable and all-consuming. So today, we’ll do something a little bit different and talk about how to cook with acorns. I promise, this will come back around to game design!

This is a stock image because a surprise snowstorm covered up the acorns I was going to photograph today. Minnesota, what a state!

A Recipe for Acorn Crepes

This fall, my partner decided to make acorn flour from this year’s bumper crop that the local oaks provided. She has some interesting insights on the process:

The gathering itself was quite easy. We just picked up the acorns and put them in a bag, avoiding any that look moldy, cracked, or have holes (an indication of weevils). It was wet the day we gathered, and I thought it might be a good idea to let them dry a bit before processing so I spread them out on a wire rack in the garage for about a week (in the mean time we had gathered a large quantity of black walnuts and left them to dry on the same wire racks). This ended up being a HUGE mistake as we soon attracted a mouse to feast on the bounty. Since we didn’t love the idea of sharing our living space with a rodent, we quickly moved on to the next step in the process.

Shelling the acorns was tedious and a bit demoralizing. I imagine that in the past a hunter-gatherer would have pounded open the hard shells between two rocks. However, I am not super invested in historical accuracy and place a great deal of value on not smashing my fingers by accident. I used a vice-grip to crack the shells and then sorted them into a small bowl of “good” nuts and a large bowl of shells and “bad” nuts. Over half of the nuts ended up being moldy, buggy, or discolored. We might have had better yield if we had gathered a little earlier in the season. The “bad” nuts got dumped on a compost pile for the squirrels while the “good” nuts went on to the next step.

I pre-soaked the “good” nuts in water to soften slightly and then ground them to a course consistency with an immersion blender (again, I assume this may have been accomplished using rocks in the past). This worked ok, but to be honest the blender struggled a bit as acorns are VERY hard and just about the perfect size to jam between the blades.

Acorns are high in tannins, which make the raw nuts quite bitter in their natural state. Beyond the gross taste, tannins can block the absorption of nutrients and can also be toxic in large quantities. Because of this it is essential to remove the tannins before using the acorns as flour. We accomplished this by cold soaking. We placed the ground acorns in a large bowl with about a 4:1 volume ratio of cold water, covered the bowl, and placed it in the fridge (yet another modern tool). About every 12 hours we filtered out the ground acorns using a clean cloth, discarded the soaking water and refilled with fresh water. At the beginning of the process the water came out dark brown. One week and roughly 14 water changes later it was light yellow. We did one last filtration and spread the course ground acorn mash on Teflon sheets to place in the dehydrator for 1 day. This was a modern tool was essential to our success. This is actually the second year I have tired to make acorn flour. The previous attempt ended in massive disappointment and frustration when the mash got moldy while I attempted to dry on sheets at room temperature—I can only imagine how many ruined batches our ancestors had in the past.

After the leached ground acorns are dried, they can be stored or further ground to make flour.

This represents about 3/4ths of the total yield of course-ground flour (minus what ended up in the first batch of crepes) from a ~2 gallon bucket of acorns.

To make the crepes, I soaked 1 cup of course ground acorns in 1 cup of water and ground further in a magic bullet until very fine.

Here’s the final recipe:

1 cup cold leached acorn flour

½ teaspoon salt

1-2 teaspoon honey (optional for a sweet version)

2 tablespoons melted unsalted butter or other fat

1 cup water

2 large eggs

The texture is firm and a bit chewy, but not tough. The flavor is pleasant but very mild.

I mixed these all up in a bowl then fried in a pre-heated cast iron skillet with hot oil. While one could make bread out of acorn flour, it does not contain gluten so I imagine it would be an incredibly dense bread and lack structural integrity. The crepes actually held up much better than I thought they would, probably because of the two eggs in the recipe. We made a savory version with toppings including oyster mushrooms form our mushroom logs, kale/garlic from the garden, eggs from our backyard hens, and tempeh bacon/parmesan cheese from the local grocery store. Even with modern conveniences it was quite a lot of work, and we didn’t have to forage the fat, salt, tempeh or cheese.

Very tasty with eggs, tempeh bacon, oyster mushrooms, and cheese!

My takeaways:

1). Past hunter gatherers likely had to be vigilant in protecting their haul from rodents. Outside, squirrels and mice will make quick work of the windfall around the oak trees. You have a window of only about a month to gather before nature cleans up. Even after bringing the acorns back to your living area you have to find a good way to protect them from insects and mice that would be happy for a free meal.

2). If one was relying on acorn flour as a staple food, one would need A LOT time as well as many bowls for cold leaching and storage.

The Little Things that Grow

So how does this relate to game design? In this case, it’s that practical experience can provide small insights you don’t get from research alone. From needing to deal with rodent raids to finding grubs in many of the acorns to the space required for leaching and storing acorns, there were all sorts of little details that rose to prominence when observed firsthand.

These sorts of details are where theme-first games like Stonesaga live and breathe. If the competing incentives are what keeps the game flowing, the intricacies are what draw people into the overall experience. These are the little moments people remember in immersive experiences. Taken together, these flourishes can inform the experience as much as the core mechanics. As I mentioned in my recent update to Stonesaga, I’ve been filling out the small-yet-important corners of the game, from the challenges and goals to the many secrets hidden in the codex.

What’s Next?

My schedule has kept me too busy to blog much of late, but I am planning to change that in 2024. I have been involved in three major projects that I am very excited to talk more about (Stonesaga and two others I can’t discuss publicly yet). And for all three, “thematic experience” are going to be critical watchwords. So I hope you’ll join me as we step forward into the new year to discuss these visions inspired by the past, aspiring to the future, and of things more distant and strange still!

World-Gardening: Building a Home for Growing Stories

For the last ten years, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about stories as intellectual property, and I’ve been reflecting on this as Stonesaga’s Kickstarter phase has gotten rolling. By intellectual property (IP) here, I mean the conceptual sprawl between a “story,” a “setting,” and a “brand.” I don’t have any answers on how to optimize a profit from an IP, but that’s OK. Instead, I’ve considered how stories expand and grow as IP. Working on Warhammer 40,000 Roleplay (Rogue Trader, Dark Heresy 2nd Edition, etc) back in the day, this was one of the first lessons I learned: “good for the story” and “good for the IP” are often at odds with one another.

What I mean by this is that a plot beat or detail that reinforces the themes of an individual work can easily clash with the wider themes of the franchise. Look no further than the Black Library novels to see how this happens. The adventures of Colonel-Commissar Gaunt are fun to read and good books, but they often soften the 40k universe into a place that feels dangerously plausible. This is intrinsically kind of contrary to the excesses that define 40k as an IP. If 40k isn’t absurd, space starts to grow for someone to ask: “Wait, are some people in this setting justified in their actions?” To which the answer is a firm “No.” 40k is about atrocity. 40k only works if it’s clear that every institution is terrible, and every individual is either complicit or powerless. This doesn’t make for the best storytelling within most individual works, and it can be very frustrating when you’re the one trying to balance these needs while telling a good story. But the whole tapestry is woven around this idea, and every incidental work that strays from it loosens the threads. The more stories that make their own best choice in a vacuum, the worse the health of the overall IP.

I saw this play out again and again over the years: on Star Wars RPG products, X-Wing ships, and more. Not in the same ways, of course. Star Wars is made of different stuff than 40k. And I got to sit on the other side of the fence when I was on the Legend of the Five Rings Story Group for a number of years, helping to guide other creators on how to fit their works into the core themes of L5R. To be clear, none of this is to say that you can’t tell good stories while cleaving to a predetermined core IP. But it’s definitely harder, and some IPs make it easier than others.

So today, let’s talk about a few trends I have noticed that help set an IP up for successful growth through supplemental storytelling. This can be licensed works, but it starts with (and often remains) fan works that drive the growth of an IP through secondary storytelling. As I go through, I’ll also try to discuss how I’ve tried to weave each of these into the narrative DNA of Stonesaga. Have I succeeded? It’s too early to tell, but I’ll be tremendously pleased if someday, people are writing secondary works about this world, so I figure I might as well make it easy in case that ever happens!

Since Spring is on its way (slowly, as I live in Minnesota), I’m going in hard on the gardening theme.

Highlight Paths to Your Core Themes

Keeping to the path should be easy and intuitive.

Or, make sure people know your IP’s core themes as distinct from the mechanics and aesthetics of the origin work. I link to my article about the heart of a game experience a lot, and I’m going to do it again. Similarly, it’s important to remember that your IP also probably has a core kernel of something that makes it special. And ideally, that kernel aligns with what you intend the IP to be about.

It's undeniably easy for people to latch onto aesthetics but miss out on the underlying themes. If you want the IP to be able to expand organically, though, it really does need to communicate the underlying themes effectively. One of the great challenges of Star Wars is that a lot of people have latched on to its military science fiction trappings over the years. And sure, “war” is in the title, but is Star Wars about war? I would argue it isn’t. This isn’t to say that a war story can’t exist in Star Wars—Rogue One is one of my favorite installments, and it’s definitely a Star Wars war story, as are the strongest arcs of the Clone Wars TV series. But, importantly, both these succeed because they bring key themes of Star Wars (interpersonal connection overcoming oppression, individual responsibility to combat societal evils) to a war story. Merely making something a sci-fi war story wouldn’t make it feel like Star Wars.

Stonesaga’s Core Themes

In Stonesaga, we’ve made an effort to really center a couple of themes, and one is the connection between people, place, and time. When a society inhabits a place, each will inevitably shape the other. And time is the dimension along which this change occurs. In Stonesaga’s mechanics, this appears in its generational play and the epochs over which the campaign takes place. But in a stand-alone Stonesaga outing of some kind, the idea that the past is closely connected to the present and shapes the future would be important to express. In a story, this could take the form of a character connecting with their history or learning something about the past from their environment that helps them to overcome a conflict in the present. The stone saga—the story that becomes part of the land itself, and recorded artistically upon the stones by the inhabitants—should be in some way key.

Set Out the Tools for Original Creation

Leave them the right tools, and people will build whole worlds around two characters who once exchanged a longing glance.

One of the best ways to prime an IP to grow is to guide people to a little corner of it that they can call their own. And one good way to do this is to set out “gardening tools,” guidelines to help people get started within the themes you’ve established. The most concisely articulated example I can think of this is in RWBY, the animated web series created by Monty Oum and Rooster Teeth a decade ago. One of the show’s core, recurring themes (established fairly directly via monologue) is how individual expression is vital to a thriving society. And this is supported directly by the simple rules of character creation for the setting, shared early in its run via social media: each character in the setting is named to evoke a color and derived from a real-world myth, story, or legend of some kind. It’s a brilliantly simple guideline with just enough restriction to create a clear pattern and more than enough freedom for people to use it to make virtually anything. For both secondary works like the novel tie-ins and fan creations, it makes a RWBY character immediately recognizable to anyone who knows the pattern, and because it dovetails with a key theme of the work, it means all stories about original characters start from a point of considering that theme.

Stonesaga’s Tools to Encourage Creativity

Stonesaga’s RPG roots make encouraging original creations a pretty natural step. The fact that you’ll be creating your own characters and society makes some of this automatic, even. But how does Stonesaga bring the themes of the game into this walking path? Well, another of Stonesaga’s core themes is around the importance of cooperation. A simple theme, but one of the great strengths humans have in facing problems prehistoric and modern alike. The character creation process encourages cooperation by rewarding players for building a set of characters with diverse abilities and traits. The more widely varied the group’s competencies, the better it will fare against the generation’s challenges. This gives each character enough of an identity to see them as an individual, and start to wonder about their personal desires and motivations as distinct from their companions. Any given generation in Stonesaga could be the subject of an RPG adventure or short story, and the way the events play out will be different for many groups based on the characters they had at the time.

Leave Room to for Things to Grow

Ask yourself “If it weren’t my garden, what spaces would seem best for planting?”

Just as important as setting out clear instructions about core themes and encouragement to create along preset paths is leaving people the space to create something meaningful of their own and bring their own ideas to the work. This is a delicate balancing act, and some IPs support it better than others. Brandon Sanderson’s Cosmere is an excellent example of setting a foundation that can be built upon in a variety of ways. While the interconnected worlds of the Cosmere have a few strong recurring themes, each world has a distinct feel, from war-torn Roshar to the intrigues of Scadrial. And perhaps most importantly, the stand-alone stories feel weighty in their own right. This means there are as many imaginable worlds as there are genres of fiction, most of them are open for exploration, and it isn’t necessary for a work to address the “big events” of the setting to feel meaningful. A galaxy is a big place, and equipped with this idea, it’s easy to find spaces to imagine a new story fitting alongside the existing material without contradicting core ideas or events. This stands in contrast to another galaxy-spanning IP: Star Wars. While Star Wars certainly can be expanded in fun and interesting ways as discussed above, the Skywalker Saga tends to loom large over any story. Exceptional efforts must be made to escape its shadow, such as the Old Republic stories or the High Republic stories. This method does work, but it underscores the core issue that a single story so thoroughly dominates the IP that it’s hard to fit anything else in edgewise without going into the distant past.

Stonesaga’s Spaces for New Stories

Stonesaga has a major advantage here, too. Every campaign will be unique, especially in the details of how it plays out. This means that, when considering future expansions of the IP, there aren’t a lot of hard lines that would interfere with other storytelling. There isn’t really even a single timeline, since events can occur in a semi-fluid order based on player choice. So anything that wanted to take Stonesaga’s core ideas and spin a linear narrative would have space to make the best choices without “contradicting” the game. On the flip side, this does mean any work in the setting either needs to commit to a single vision of how events played out (as the Mass Effect tie-in novels do, for instance), focus in so tightly on single events that it isn’t an issue, or assume a (textual or metatextual) multiverse approach. This is also a place where, were Stonesaga to expand beyond the single board game to other works, there might be important choices to make. Perhaps the best thing for the board game (fluid, flexible story development) wouldn’t be the best rule for the IP moving forward. The board game attempts to express the IP’s themes effectively, but, like anything else, makes concessions to its medium.

Of course, as I like to say, we’ll burn this bridge when we come to it. If we get to the point where Stonesaga needs an IP bible, I’ll just count myself happy that we’ve gotten that far! In the mean time, if Stonesaga catches your interest, check out the ongoing Kickstarter!

Stonesaga: Going with the Flow

This is an expanded version of a designer diary posted on BGG. Hopefully folks find the extra commentary interesting!

Whether you’re designing a competitive 1-v-1 game, a cooperative story game, or a roleplaying game with a GM and players, one of the most crucial yet elusive parts of game design is finding your game’s ideal flow.

In broad terms, flow is the pacing of the game, the way in which one action runs into the next to form a cohesive and (hopefully) satisfying experience. In chess, the flow is a series of back-and-forth actions that cause the board state to progress. Each action has tactical ramifications, and in aggregate, all of the actions have strategic consequences that eventually lead to the game’s outcome. The fact that chess includes rules to prevent repeating board states indicates that each action changing the board meaningfully is important to the flow of chess. It isn’t enough that an action is tactically interesting, it must also contribute to the strategic progression of the game.

Flow(chart) of Priorities

Obviously, Stonesaga’s flow isn’t going to look much like that of chess. Stonesaga is cooperative, highly evocative rather than abstract, and grapples with very different themes and concepts from chess. But, like chess and a lot of other board games, Stonesaga does present a player with multiple needs at once and numerous ways to address them. Chess’ different needs are tactical (how to the most out of one move), strategic (how to progress the board state favorably over multiple moves), and interpersonal (how to learn about the opponent through the strategic progression), and the toolbox a player has to address them are the many different moves each piece can execute.

To understand Stonesaga, we need to begin by looking at what it encourages players to achieve during each game. Stonesaga’s competing needs can be mapped as follows.

Immediate needs include taking care of your own character’s basic requirements. This means gathering food and water to recover energy, finding shelter to ward off the elements, and making fire to protect yourself from the valley’s icy nights. Fulfilling these basic needs will usually consume at least some of your group’s energy.

Time pressures come in the form of activity (which increases each night, can trigger new events, and eventually end the game), unrest (which increases when you and your society are at odds), the behemoth, and goals you can only complete in your current game. These give you incentive to act on a more strategic level, avoiding problems or completing goals to progress toward the end of the game on your preferred terms.

Finally, curiosity and progress provide a third pillar of motivation to continue exploring the world, investigating omens around you, and crafting new items and structures that will persist into future Challenges, giving you a leg up in later games.

There are other ways one could break down these needs (such as with a hierarchical model), but just thinking about these three categories helps underscore why the choices in Stonesaga often become difficult. Do you want to make progress on a future accomplishment at cost to your current status? How do you manage the time pressure against your immediate needs while still learning more about the valley and its secrets? These are the questions that make for hard but interesting choices, reward players who consider their options carefully, and will ultimately make different players’ experiences quite varied based on what they chose to prioritize and how this shapes their society and world.

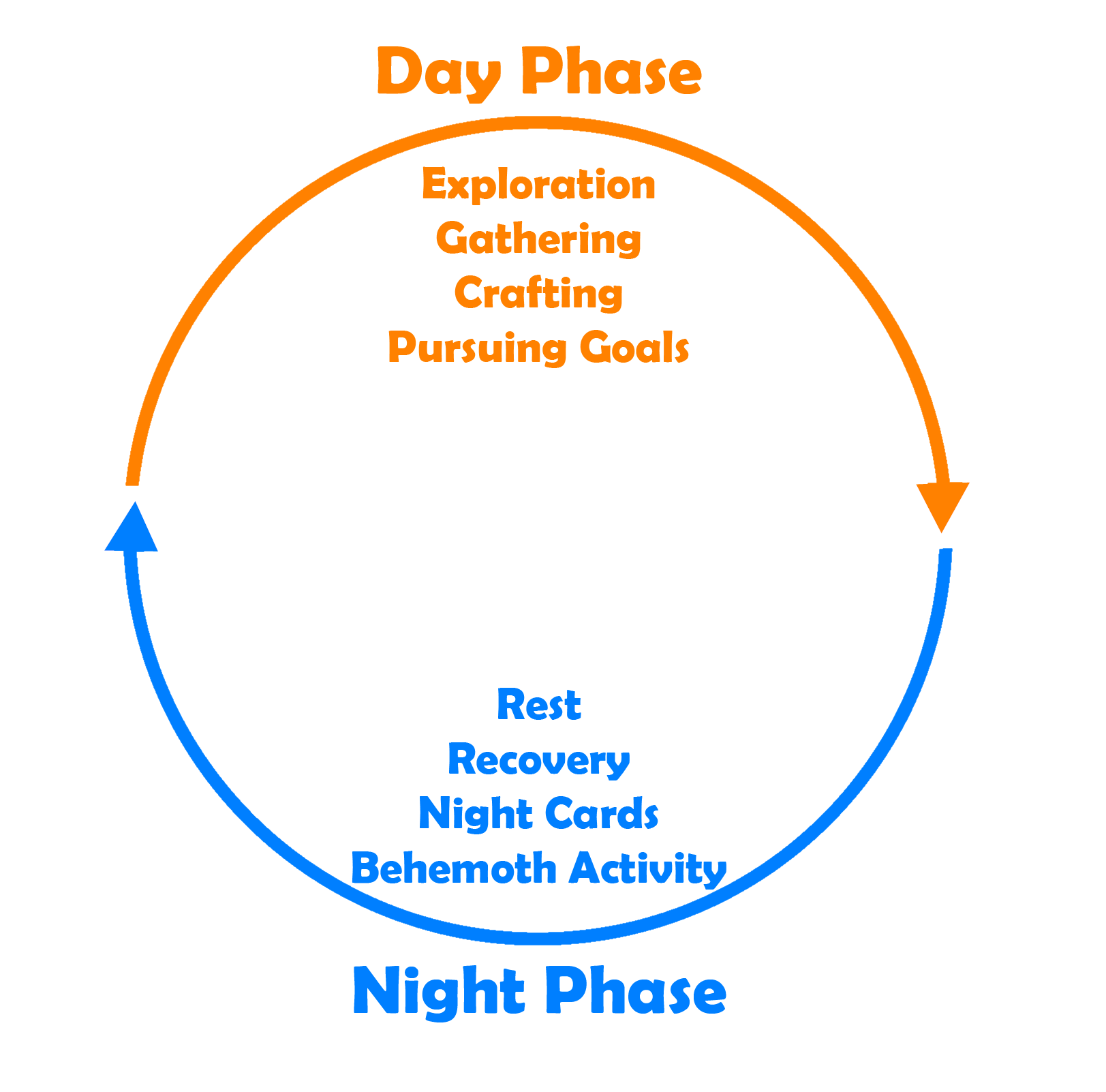

If immediate needs are basic upkeep, activity is the clock that keeps people moving toward their Goals, and curiosity is the force that draws people to step off the path to learn the game’s hidden secrets, the Day/Night cycle is the arena in which these motivations compete.

The Cycle of Play

Each game of Stonesaga (a Challenge) takes place over multiple Day and Night phases. Days are the character’s chance to act on the board by spending their energy, while nights both gives character a chance to recuperate and also toss new problems their way that reward proper preparations.

During each day, characters can take actions that contribute to filling one or more of these needs. Each action costs 1 or more Energy, and characters can take multiple actions per day so long as they can pay the energy costs.

Characters can explore the map to find new terrain features, which gives them a wider range of options for gathering resources. Some resources, like food and water, fulfill immediate needs. Others help complete Goals before the activity track ends the game. And still other resources are needed for crafting new items and structures.

However, it’s hard to fulfill all of these competing needs in a single day. This is where choices get interesting. Gathering water reliably provides 2 water for 1 energy at a water feature like a river or lake. But foraging and fishing, which cost 2 energy, can provide water if the character gets lucky, and might also provide other resources at the same time. Players must weigh the risk against the potential return of their action, as well as the options that are available in their current hex and nearby hexes they can reach in a few moves. Additionally, while gathering water is safe and reliable, foraging and fishing can provide insights into the valley’s secrets that the safer, lower-cost action can’t through investing omens or reading codex outcomes.

Every night, characters must face consequences of their decisions during the previous day. First, characters rest and recover energy. The more of their immediate needs they met, the more energy they will have available to use the next day. Further, meeting these needs helps characters recover from disease and injury, and generally prepares them better for the next day.

Characters must also draw a Night card each night (or possibly more than one, if they have spread out on the board). This Night card showcases the dangers of the valley: blizzard conditions, dangerous predators, and unexplained happenings can all befall the characters. Many of these cards have bonuses for making the right preparations, however. Clothes, shelter, fire, and other tools can be key to coming out of the night unscathed. The Night card also changes the omen and increases activity. This can trigger new events that might impose difficulties on the characters and pushes the Challenge further toward its inevitable conclusion.

Finally, once it is present, the behemoth acts at night, pursuing whatever agenda it may have in the valley. As the characters’ society grows to understand the behemoth better, the players may devise methods to minimize or even benefit from the disruption this massive creature can create. Many of the long-term projects characters can pursue over multiple Challenges, like the acquisition of lore and creation of items, can help make dealing with the behemoth easier or open up new options that did not previously exist. This is one of many ways the game rewards the pursuit of player curiosity, as there are more options to address the challenge the behemoth presents than that it might seem at first, but uncovering these options requires diving deep into the secret lore of the valley or inventing new technologies to circumvent problems the behemoth creates.

The Tug of War

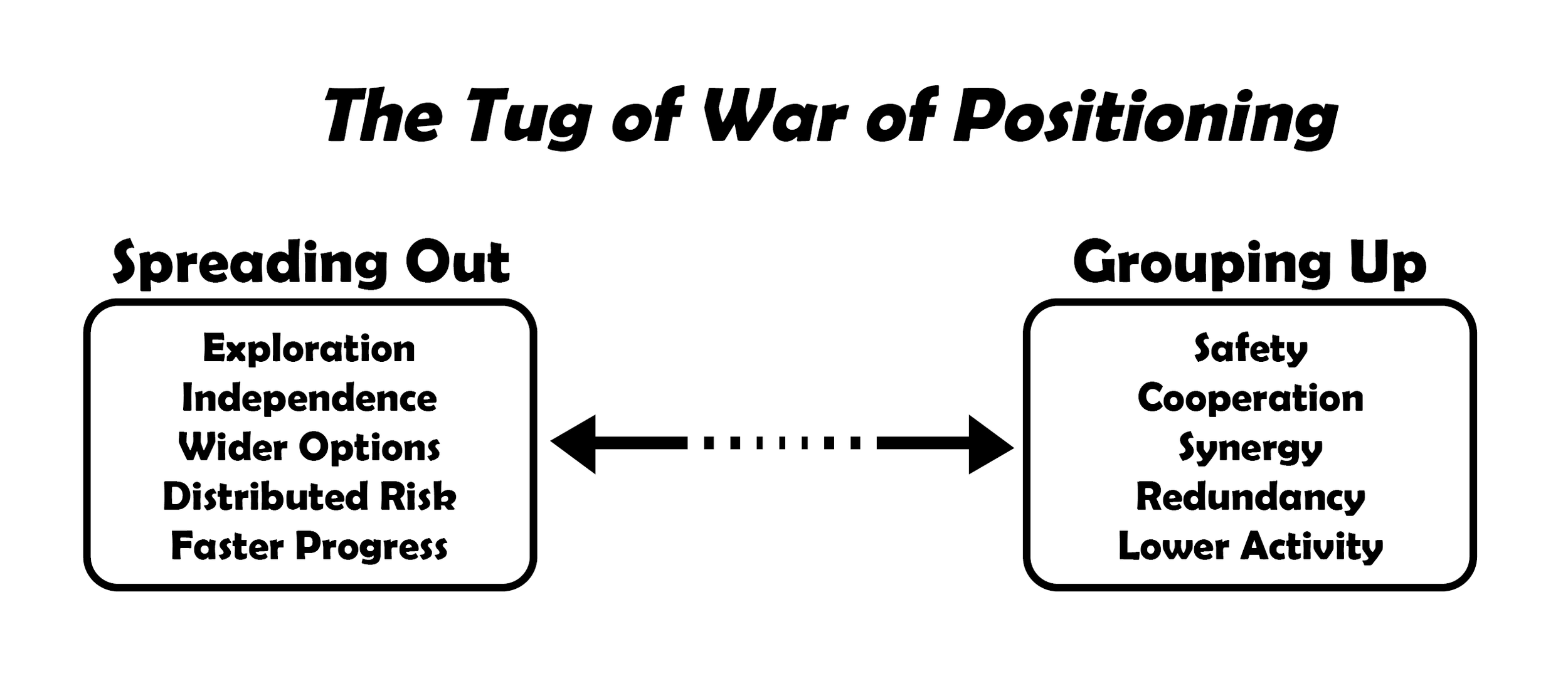

One other key element of Stonesaga’s flow of play is the competing incentives between clustering up in the same hex to cooperate and the desire to expand outward and discover many hexes.

Spreading out has some key benefits. It gives players a chance to find new things that help solve the group’s problems. It also fulfills a desire many players have to explore. It creates a wider net of option for the group, which can make acquiring specific resources and achieving particular Goals easier (or even make previously impossible Goals possible).

Further, it distributes risk, as each character is unlikely to be affected by the problems the others encounter as they explore and weather harsh nights. It also decreases the risk of failing to find key assets. If the group really needs a forest to harvest a particular resources, spreading out is far more likely to uncover that feature quickly.

However, there are also critical advantages to staying close together. Being in the same hex allows characters to share resources and use beneficial abilities on one another. It also lets characters share helpful assets like shelter and fire, meaning the group can dedicate less energy to fulfilling these basic needs for everyone.

It also provides lower activity increases, as fewer Night cards are drawn. While there is a chance all players will be subject to a particularly rough draw that affects everyone, the group will have more time to finish their Goals before the game ends if they end every Day phase clustered up.

A Work in Progress

Stonesaga’s flow of play hasn’t yet been perfected. While playing the Beta has made me feel very confident about the overall concept, the devil of such things is always in the details. The balance of activity rewards, Night card effects, density of features on terrain hexes, and activity tracks on Challenge cards are still under close evaluation. If you’ve had a chance to try out the Beta and have thoughts on the flow of the game and how to polish it even further, please leave us a feedback form about it or drop a message here. There’s still a lot we can all learn about Stonesaga as we move toward the best version of the game we can make together!

User Questions

Overview: This is part of an ongoing series of articles on the design of a new board game that I am working on in partnership with Brendan McCaskell and OOMM Games. Throughout these posts, I want to give readers a sense of my design process, as well as some of the ruminations that came out of work I was doing at each stage. Check out the introduction to this series here, and my discussion of the game’s minimum viable prototype here. Today, I’m answering some basic questions about the mysterious Codename: Lithotaph that people have asked me so far!

Q: What type of game is it?

A: It’s a cooperative exploration and survival game. Players take on the role of members of a hunter-gatherer society moving into a glacial valley recently opened by thawing ice. They must work together to achieve shared goals, navigate perils to their civilization, and survive the massive, immortal beasts that have also entered the valley. As they explore the valley, new hexagonal tiles are added to the valley to represent the locations they explore, and this map persists from game to game by fitting into the game’s custom trays.

Over a campaign of linked games, players chronicles events in the lives of new generations of characters, creating a tapestry of connected stories over numerous generations and several epochs.

Q: How many people can play?

A: At present, the game supports 1 to 5 players. These can be the same players over multiple games, or players can come and go on a game-by-game basis.

Q: What is the complexity level of the game? What age range is it appropriate for?

A: The game is targeted at what I’d term middle-high complexity. What does that actually mean? I’d say it’s comparable to Betrayal at House on the Hill or Pandemic – it has a relatively simple core loop of characters moving around a map and taking actions, but a lot of emergent events the game presents that someone needs to read and understand. In terms of age range, I’d say probably “recommended for 12 and up?” But I’ve met a lot of ten-year-olds who would do fine with it. Like a lot of co-op games, if one person is very familiar with the rules, they can make the experience smoother for others who are newer to the game.

It’s also a campaign game, intended to be played over numerous game sessions. While individual game sessions are meant to be more stand-alone than a typical Legacy game, it is best enjoyed through repeat plays in a persistent world.

Q: What are the key ideas behind the game?

A: The key concept is one that arose from the original discussions of painting on a cave wall: it’s a game about leaving your mark. More broadly, it’s a game about how humans change their environment, and how they change to adapt to it. The choices you make will affect how your society’s culture develops, which in turn will impact future generations and the challenges they face and decisions they must make.

Q: What do you do in the game?

A: Each turn, your character moves around the map, interacts with terrain nodes by playing various minigames to gather resources, crafts new items and buildings, or pursues specific goals set forth by the game scenario. Over the course of a game, players must work together to attempt to complete key societal goals and prepare for the coming of a titanic, primordial creature that might threaten their people if left unaddressed.

Q: Mini games?

A: Resource-gathering, crafting, and even inventory management take the form of minigames. For instance, foraging consists of a simple trick-taking game of finding supplies in the woods while avoiding the attention of lurking predators. Meanwhile, inventory management requires physically fitting your supplies and craftable materials into the bag outline printed on your character board. Each minigame is intended to engage different types of players, so that everyone can find some area they really enjoy!

Q: Why have a generational gap between each game?

A: This game is about societies, environments, and their relationship over a long period of time. As such, I feel it’s important that no single character play too big a role within the story that unfolds over numerous games. A character who is “young” in one game might be “old” in the next, but after that, they’ll cease to be playable. However, they based on their actions, they might continue to exist as a saga, becoming a story that inspires new generations.

Q: How many play sessions will it take to complete a campaign?

A: To play through a single campaign, players should expect somewhere in the neighborhood of twelve to sixteen game sessions. These game sessions are divided into several epochs, each of which consists of 3-4 games.

Q: Why divide a campaign into epochs?

A: First of all, it’s a way to add gulfs of time, creating an even more substantial scope to the story. While there might be 20-50 years of in-game time between each game session, epochs could be separated by centuries or even millennia. This allows the glacial valley – and the people within – to undergo radical shifts, adding further variety to gameplay and storytelling.

Second, it creates a set of neat “break points” at which a group can shuffle its members or even just take a week off to play something else. Each epoch can serve as an “onboarding point” for new players, and each one serves as a soft reset during which the consequences of players’ past decisions play out to shape the new epoch.

Q: How does the game evolve across multiple gameplay sessions and epochs?

A: In the first game, your goals are simple: find sources of food and water in your new home, create a stable encampment, and survive your harrowing first encounter with a primordial creature that has made its way into the valley at the same time you did. However, as the game goes on, your society will be presented with choices based on the results of past games. These choices will affect future goals. For instance, if you are given the chance to choose between reinforcing a settlement or fleeing from a threat, the former might lead to a game where you need to batten down the hatches and survive a siege by a primordial beast while the latter might require creating tools you can use to move your encampment somewhere safer.

Across epochs, these choices will unlock larger divergences in your society, such as giving you access to different technologies, ways of organizing your society, and means of subsisting.

Q: Is this a legacy game or not?

A: It has many similarities with Legacy games, but there are several key features that differ from the way the model usually works. We’re calling this model “persistent gameplay.” While players do permanently mark a few components such as a character cards and their journal, most components can be rest to their original game state. For instance, the board uses interlocking tiles held in trays to create a persistent map – but if players wish to fully reset the map, they can do so by popping out all of the tiles. The components that are permanently altered are those that can most easily be replaced – character cards and the journal.

Q: Where can I get it?

A: The game is still a ways off from being available. OOMM Games will be running a crowdfunding program for it sometime in the future, But don’t worry, I will be absolutely, intolerably vocal about it once the campaign begins!

Q: Will it have miniatures and/or a hobby component?

A: The game will have some miniatures, which likely will be unpainted. Additionally, some of its components will be plastic rocks with a texture for players to feel (this is a necessary gameplay element), and could be visually spruced up with a base coat and drybrush.

Q: What is the world of the game like?

A: The game takes place in a fantasy world that bears some similarities to our world during the Mesolithic era, but with a decidedly fantastical bent. There are unfamiliar creatures that populate the world, strange materials with properties like nothing on Earth, and giant, immortal beasts that roam the land, sea, and skies. We wanted players to feel like explorers in this valley just like their characters, delving into a wholly unfamiliar ecosystem and finding their own place within it.

Q: What is your favorite mechanic so far?

A: It’s not one mechanic, but the flow from one game into the next is the set of mechanics that are most important to the game in my eyes. With that said, I am also very happy with how the crafting system has come together, especially with Luke Eddy’s contributions.

Q: Can I playtest it?

A: If you’re interested in playtesting, details will become available with the Kickstarter in Q3 of this year. However, if you’re really gung-ho to play, you can send an email my way!

Bonus Questions about Other Things:

Q: What is your favorite piece of design from the Razor Crest for X-Wing?

A: The Child. That card took a shocking amount of work to get right, but I think people will have a lot of fun building various baby carriers.

Q: What other projects are you working on?

A: Oh, that’s such an interesting topic! I just [the rest of this entry has been redacted]

Q: Where's that Journeys RPG adventure you promised on Twitter?

A: I’m working on it, along with an updated version of the Journeys rules (the current version is available here). I promise! I’m in the midst of spinning up the playtest for both.

Q: What games are you most excited about right now?

A: I recently picked up a Kill Team set, and am looking forward to getting more games in. I also have been getting into Saga: Age of Magic with my old WHFB Tomb Kings. I played a bit of X-Wing with some custom ships earlier this week, too! Brooks Fluguar-Leavitt has also gotten me quite hyped to try Osprey’s The Silver Bayonet.

2021: A Year in Review

Well, if 2020 wasn’t the year I expected, 2021 was… a year in which the only sure thing seemed to be instability.

What did I get up to in this year of predictable uncertainty?

Freelance Work

I’ve done a lot of freelance work in 2021, primarily on three projects, two of which I can discuss.

The first is Adventures in Rokugan, Edge Studios’ project to bring the world of Rokugan to the experience and mechanics of 5e. This project was a lot like the job I did for years on the RPG team – coordinating with (fellow) freelancers, with Sam Gregor-Stewart, and with the folks at Edge, designing a few core elements for a mostly complete RPG system, and developing a ton of content for said system.

Adventure!

I had never professionally developed in 5e before (though I’ve played in it plenty), and it’s an interesting challenge. The syntax for its mechanics is quite elegant but very subtle – it works as hard as possible to create repetitive structures while seeming as much like natural language as possible. For example, did you know that 5e makes heavy use of contractions? It’s almost always “can’t” instead of “cannot.” This might not seem surprising, but it’s fairly uncommon in games technical writing for whatever reason. Similarly, when presenting an idea, 5e almost always explains the concept, then carves out exceptions after explaining it. If an ability can’t be used on spells “with multiple targets,” it won’t use a parenthetical or inset clause to explain that concept. Instead, after giving the short version, it will include a full explanation carving out the exceptions with examples. This means explanations tend to be wordier, and if you stop reading the paragraph early, you’ll miss key information. Both of these choices create a conversational tone, which is especially noteworthy because of how much it departs from the mechanistic, concise wording of 4e. I’d been playing 5e for years, but until I developed in it, I never consciously realized these things.

The second freelance project I’ve spent most of the year working on is Codename: Lithotaph. I’ve been chronicling my journey working on this game in a design series, but designing a board game from the ground up has been thrilling, to put it lightly. It has been especially amazing watching the game come to life with art, graphic design, and content design falling into place as Brendan and I have assembled an awesome team for the project!

It’s amazing what getting actual artists and graphic designers about does for a game!

One interesting thing I’ve learned about freelance projects, overall, is how much of one’s time as a freelancer ends up dedicated to the logistics needed to make projects happen. This isn’t intellectually surprising to me, but a lot of my freelance design time was spent on pitch decks, reviewing legal documents, talking to lawyers, and communicating with clients. I happen to find this work pretty stimulating, but for those looking at getting into design as a part-time or full-time project, my advice after 2021 is “build more time than you think you’ll need into your schedule for the vital task of document prep and review.”

Game Design Blogging

My game design blogging was, to put it generously, frontloaded toward the first half of the year. This is at least partially because I was busier with the actual design work I write about in the second half of the year. It is also partially because my initial pace was creatively unsustainable. After nearly a decade at Fantasy Flight Games, I had a ton of bottled-up ideas about design I wanted to share but had never had time to publish. I churned through a lot of that backlog early on.

Still, I’m pretty happy with my output across the year. Here are a few highlights (I’m cheating in a few from late December 2020 because they were hits):

My perspective on the competitive mindset in games, especially X-Wing

Design techniques to motivate players to use (and enjoy!) your game mechanics

An ongoing design series about one of my current projects, Codename: Lithotaph

Personal Game Design

Between the above two categories, I’ve found less time for publishing free games than I imagined I might have back when freelancing was a new, shiny world of possibility. I did manage to to get my X-Wing/RPG Compatibility Guide together and out, though! It’s also a guide for making custom homebrewed pilots, if that’s a thing you want to do.

I have a number of mostly finished simple roleplaying games sitting on my computer that I want to put on my website and perhaps on itch.io for 2022. I just need to hit them with that last bit of polish, which is of course always the most protracted step and even starting it can be intimidating. Still, I’m curious to get a bit of insight into the logistics and economics of Indie RPG PDFs. It’s obviously a vibrant artistic space, but one I’ve always observed at a distance. I’d like to put a few of my concepts out there to get a sense of the field.

I’ve also been working on the Journeys campaign I’m going to run in the new year, including an update with some new features. Like punching!

Any excuse to raid the Getty Open Access Collection.

Hobby Stuff

Ha ha hah. I have been looking on with envy at everyone getting incredible pandemic armies together for Warhammer 40k and other games while my sad Space Wolves sit, not-quite-finished. It turns out I got 60% of my painting done as a social activity and the other 40% in wild, pre-tournament sprints. With casual indoor hobby-shop gatherings off the table most of the year and no tournaments, I got almost nothing done in this sphere.

The best thing I can say to defend myself (wait, why do I need “defending” from not having pursued my hobbies sufficiently?) is that I made some homebrew cards and dials to go with the Battlestar Galactica ships I painted as a gift last year. I also got in the game with them I’d promised, even!

The battle did not proceed well for the Cylon Empire.

Personal Life

The pandemic remains trying, but I’ve been very lucky so far. I’ve been able to get vaccinated and boosted without horrendous waits, for which I count myself very fortunate. I have a job that doesn’t require me to leave the house, and can minimize my risks in most contexts. I miss going to events – running con games and seeing the X-Wing, Armada, and Legion Communities with their stuff on display was always a lot of fun. I look forward to getting back into the swing of things… someday, but I’m also not holding my breath that it’ll be soon. It’ll happen when it happens.

Overall, I’m well. I don’t get into a lot of personal life specifics here and I’m not going to start now – this is fundamentally a website for my professional life – but a lot of folks I’ve communicated with this year have made it clear they care about me as a person, not just about my work and output. I appreciate that! I hope you’ll keep reading and keep reaching out as we move into 2022 and see what this new year brings!

Minimum Viability

Or, Design Series Part 2.

Overview: This is the third of several articles on the design of a new board game that I am working on in partnership with Brendan McCaskell and OOMM Games. Throughout these posts, I want to give readers a sense of my design process, as well as some of the ruminations that came out of work I was doing at each stage. Check out the introduction to this series here. Today, we’re delving into the creation of a minimum viable prototype of a board game, and how to avoid doing to much, and what to do when you do too much anyway.

What is a Minimum Viable Prototype?

Pictured: Everything but the kitchen sink, which is behind me.

For board games, I define a minimum viable prototype as the set of the fewest number of components that are needed for a player to have the experience of playing that game. For a minimum viable prototype, I am taking as an assumption that you, the designer, will be at the table, and can act as a living reference guide. This means that only the components that you cannot adequately act to replace on the spot are needed. This is somewhat subjective, and deciding whether an element is superfluous or vital depends on knowing what you want the heart of your game experience to be.

For a concrete example, a minimum viable prototype of chess would likely be a board and differentiated markers with piece names written on them. As the designer could explain each piece’s special rules and the general rules for the game, a rulebook would be superfluous for the minimum viable prototype stage. The designer would have to decide whether or not aesthetics are an integral part of the experience they wanted to create with their new game of “chess,” which would determine whether or not some sort of graphic simulation of the eventual pieces would be needed – but given what we know the experience of chess to be today, I think one could reasonably dispense with them and use just text to differentiate pieces.

For Codename Lithotaph, pictured above, one example of planning to the needs of the minimum viable prototype was laminating the terrain tiles. Suddenly, any token or marker could be replaced by simply writing on the tile with a dry-erase marker, saving me needing to make tons of tokens for the various terrain types, statuses, and other elements the terrain tiles might take on during the game.

As a sidenote, if you’re building a minimum viable prototype on Tabletop Simulator, substitute “digital” for “physical,” but if you intend for your game to be physical in the long run, I personally find it pays to actually go through the arts-and-crafts early, for some reasons I’ll discuss below.

When Is Going the Extra Mile Necessary?

The numbers are because there is a 0% chance I’d have glued the fronts/backs together correctly without them. Know your strengths and weaknesses!

A key objective of the minimum viable prototype is to be… minimal. It is right there in the name, after all. Why is that important? Because if your design process is anything like mine, you’re going to iterate a lot at this stage. The image of a squirrel digging through a dumpster, haphazardly tossing half-intriguing scraps in every direction, springs to mind. So getting each version’s minimum viable prototype to the table quickly is important, and any given element you spend a lot of time on might not be worth keeping.

But sometimes, you need to feel a specific component in your hand to know the experience it’s going to create. That’s where you occasionally need to risk overdesigning a bit because it’s important to the game’s core.

For Project Lithotaph, I knew that I would need a set of board tiles that looked at least decent to get the feel for how the game would come together. Exploring the valley is a huge part of this game, and placing tiles together to form a map is the main way the game draws players into this experience. I am not a (good) graphic artist, but I have basic knowledge of a few image editing programs, so I drew up these tiles.

I then spent a lot of time printing these out, cutting them , and gluing them onto punchboard before realizing the really obvious problem…

Making the Best of Going Too Deep

So you screwed up creating a regular hexagon…

One thing I’ve found is that sometimes I need to overindulge on details at this phase. Or maybe it’s more apt to say I’m going to do it whether I intend to or not. But whatever the case, the experience of the sort of games I make comes alive in the details. What do I do when I’ve made some component, spent two hours cutting, gluing, and cutting again only to find the hexagons don’t fit together?

This is where I had to decide whether the remedy to my screwup was decide it’s good enough for now or reuse what I can but cut my losses.

A lot of the time, good enough is your friend for a minimum viable prototype. When I changed the name of “stamina” to “fatigue” before the first test even happened, I didn’t reprint the components corrected, I just told people “stamina is fatigue” when we played. When I eliminated whole systems from the prototype because I realized they weren’t core at this stage, I just crossed out references to them on components I’d already printed. These issues were nuisances that didn’t interfere with the core experience. Aesthetics are important, but so is getting the prototype to the table.

But the tiles not fitting together was a bit different. I could already see the writing on the wall that that was grit in the machinery of a key system, and it was going to cause real friction that the final game obviously wouldn’t have, distinctly changing the experience of playing the game. Since I was after seeing how well the desired experience I had in my head came out of the game I had drafted, I knew I needed tiles that actually fit together. So I pivoted: what was the least amount of work I could do to make the irregular hexagons work? I initially cut one down to a regular shape (always repurpose when you can!), but that proved to be more effort than remaking them entirely, so I ended up cutting my losses and remaking them and tossing the last set back into the Big Box of Prototyping Components for some future project. Who knows, maybe I’ll even need irregular hexes someday.

What’s Next for the Codename Lithotaph Design Series?

Next article, I’ll be taking a break and fielding some questions! Curious why the Codename is “Lithotaph”? How I organize a my files? Designers and games I find inspiring? Whether I like cake or pie better?

Hit me up at my email, or over on Twitter, with your questions about my game design process, this project, or other topics!

Wilderness of the Unwritten

Or, Design Series Part 1.

Overview: This is the second of several articles on the design of a new board game that I am working on in partnership with Brendan McCaskell and OOMM Games. Throughout these posts, I want to give readers a sense of my design process, as well as some of the ruminations that came out of work I was doing at each stage. Check out the introduction to this series here. Today, we’re delving into the early stages of design, and the importance of guiding documentation in game design.

The Sphere and the Cone