Agency and Futility: Three More Studies in Board Game Existentialism

Last week, I discussed the matter of Candy Land, existentialism, and how agency does (and doesn’t) factor into the experience of that game. But the term agency itself can be a bit of a buzzword, ascribed different meanings as context requires. Particularly in discussions online, “agency” can end up meaning a lot of things to a lot of different people. And almost all games set out at least some parameters confining the behavior of the participants and possible outcomes, so what even is “agency” within the context of a game? And perhaps more importantly, what design choices can make people feel like they have lost it?

The definition of agency that I work from is this: agency in a game is the feeling that you had the ability to make a meaningful choice between options presented to you by the game.

The key word in this whole setup is feeling. What people describe as agency isn’t as simple as “your choices influenced the outcome,” for a couple of reasons I’m going to get into below.

Options and Impact

Although if video games have taught me anything, maybe I shouldn’t trust the offers of free cake…

Feelings of lost agency (or “futility”) aren’t limited to Candy Land (where you have no choices) or to scenarios where the choices you make don’t actually influence the eventual ending enough for most people’s tastes (Mass Effect 3’s ending). They can also arise from situations where you make choices, but the options aren’t constructed to make those choices feel meaningful.

If you can choose between three things, but one is obviously the best choice, it hardly feels like a choice at all. Candy Land actually contains a variant rule “for older children,” which allows you to draw two cards and choose. This is interesting, because it unquestionably adds agency in the dictionary-definition sense to the game: your choices now influence the outcome. But would an adult feel like that choice was meaningful most of the time? Probably not. The correct choice will almost always be obvious immediately. While having an easy correct choice in a game is fine sometimes (and can even be good in small doses), if the entire gameplay loop is easy correct choices for all players, it’s going to feel just as inevitable as the one-card version because nobody is going to make a mistake. This is the Tic-Tac-Toe problem: once a player becomes good enough at the game to always make the optimal move, the only way to win is not to play. Mind you, this doesn’t make Tic-Tac-Toe a bad game, just one with a limited lifespan for most players. This is also why many games with staying power have some amount of randomness (cards, dice) or uncertainty (simultaneous hidden choices) ingrained into their formula. Like a little bit of salt in a sweet recipe, a small amount of randomness can actually enhance players’ feelings of agency by making the “correct” option harder to determine and thus make the choice more satisfying to untangle.

Expectation and Feedback

Yeah, technically it’s what you were promised, but it doesn’t really feel like it’s in the spirit of the options presented.

Perception of agency can also be undermined when a player’s expectations for the results of an action fall out of line with the actual results. Even when an option you pick advances the game state in a substantive way, it can feel futile if it didn’t do what it advertised.

In games like X-Wing, sometimes you have choices that are tactically impactful but nonetheless feel like they didn’t do much for you. For example, the M12-L Kimogila’s “Dead to Rights” ship ability triggers only when attacking a foe in its bullseye arc. When you pick a Kimogila for your list or pick a maneuver on the table, you imagine getting to use that ability. But your opponent is likely aware of the ability, and will work to avoid it. If your opponent is forced to take otherwise disadvantageous moves to avoid you getting a substantial bonus, your prior choice was undeniably impactful on the outcome. Your opponent had to change their behavior, and you gained a benefit from that change. However, because you didn’t get the benefit you imagined, it can feel as though your choice “didn’t matter.” The game isn’t giving you the expected feedback that your ability “worked,” so it can be easy to overlook how your choice affected the game’s outcome. In this case, one player might even feel like their opponent’s effect was “oppressive” while the other felt it “didn’t do anything.”

For an ability to feel like it is making a choice meaningful, it must give the player feedback they can interpret – and players at different skill levels will interpret feedback differently. Inexperienced or less focused players might not be able to detect feedback from the game that veterans notice quickly. Of course, calibrating feedback can be a difficult line to walk in competitive game. Abilities that can be mitigated through good play by the opponent can feel futile for the player using them because the game didn’t give them any feedback that they had used the ability successfully. But abilities which result in a clear good for their user regardless of the opponent’s action create feelings of futility for the opponent. This isn’t really a “problem” that can be “solved” through a clever design trick so much as a scale that needs to be balanced.

Eyes and Beholders

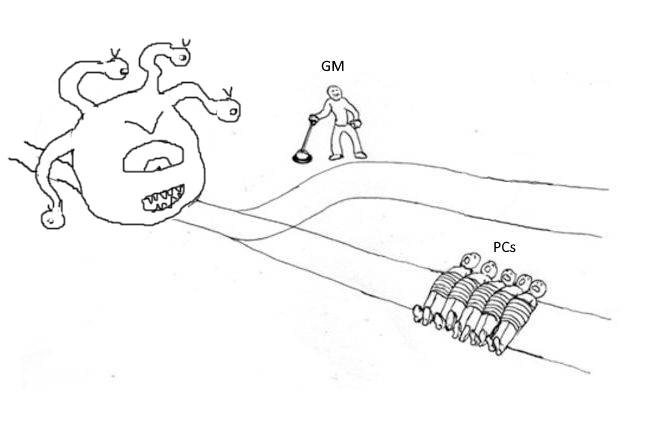

This isn’t quite what I was thinking of when I said “railroading”!

When it comes to rules writing, form and function are hard to disentangle, and presentation matters a lot. Something as fundamental as the way the rules are presented can have a major impact on players’ feelings of involvement in their destiny. Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition and Apocalypse World provide an excellent example of how conceptual organization can affect players’ perceptions of agency.

In D&D 5E (and many, many other RPGs), the game describes how to resolve various example actions players might attempt during an adventure. Perform an attack, leap a distance, disarm a trap: each has a section of the rules that details how this might occur. It then gives the GM explicit permission to extrapolate from these examples. Whenever a player wishes to attempt something in the narrative, the DM refers back to the examples, finds the one that fits best, and either asks the player to do that or something similar, modified as they see fit by narrative circumstances. When the GM asks “What do you do?”, the player can describe whatever they wish. The player’s options are, theoretically, limitless. The GM then translates this into something that the game engine can process, and asks the player to roll the appropriate dice. The system rests upon “permission” of the GM, with players putting a large degree of their agency and trust in the hands of this individual.

In Apocalypse World and its various successors, the game describes to you how to do various things as “moves.” Each move encompasses a set of actions, such as performing an attack, leaping a distance, or disarming a trap. But critically, the moves are stated by the game to be a comprehensive list, and GMs are discouraged from allowing anything outside of the listed moves or from preventing players from using moves as-written. They are intended to be the only options. Some of these options are so open-ended that they could encompass virtually anything the players might conceive to do. But when the GM asks the player “What do you do?”, the player answers “I use this move to…” and then describe what they wish to accomplish.

From a certain point of view, players have considerably more agency in Apocalypse World. One of the traditional places RPGs suffer from agency issues is in the GM’s act of translating player desire into in-game activity. If the GM doesn’t understand what the player wants, or just fundamentally disagrees with it, the player may end up with a result that isn’t impactful, or that they didn’t predict (the problem cases discussed above). Apocalypse World explicitly limits the need for the GM to act as an intermediary between the players and the world of the game, putting that power directly into the players’ hands. Obviously, many people like Apocalypse World for this very reason.

But many other players report feeling as though they do not have as much agency as they desire in Apocalypse World, because if they ask for something the system did not account for, the GM does not have the explicit authority to simply make it so. For some players, the existence of a complete, preset menu of options is antithetical to the wide-open sky of possibilities RPGs are often said to promise. Even if you have an option that can “do anything,” being funneled though a set of specific options to reach it can feel constraining to some people. The theoretical set of possible outcomes could be very similar to an outside observer, but the process by which the players reach those outcomes affects not just their experience, but which options they pick and why.

What we have on display is two different forms of agency. The different frameworks give different kinds of freedoms and limitations. One favors the ability to create anything, but requires compromise on the final outcome,. The other offers the ability to create within preset confines, but without compromise. Which one gives players “more agency?” That answer is in the eye of the beholder, based on what they personally value. As a designer, you need to consider what forms of agency your game values most, whether those mesh with your game’s themes, and then how your game communicates that agency clearly to the players so that their expectations are not disappointed.